Investments that seem riskier appear like they will make higher returns. But if high-risk assets always gave higher returns, they wouldn’t be high risk.

Key Takeaways

- Modern portfolio theory claims that risk is volatility. This is clearly false.

- Generally, if there is a huge rise, a fall will occur and vice versa. Regression toward the mean is a general rule of market cycles.

- A good economy makes stocks go higher because businesses make more money.

- India is likely to be the next China. Then Nigeria and Bangladesh.

- Success in investing is not only about being correct, it is about being more correct than others. If everyone thinks one asset is great, then it won’t perform as well as a contrarian but correct investment.

- Central banks (like the Fed) mainly exist to control inflation.

- Since inflation results from economic strength, the efforts of central bankers to control it amount to trying to take some of the steam out of the economy. They can include reducing the money supply, raising interest rates, and selling securities. The problem here is that these methods limit the growth of the economy.

- The bottom line is that most central bankers have two jobs: to limit inflation, which requires restraining the growth of the economy, and to support employment, which calls for stimulating economic growth.

- Governments use fiscal policy (taxing and spending) to manage the economy.

- Politicians are incentivized to spend on programs that will get them votes.

- People thought that newspapers were “defensive” stocks that wouldn’t go anywhere. But then the internet disrupted them.

- “In 1999, investors accepted at face value their telecom companies’ rosy predictions of the future, and they were willing to pay handily for that potential. But in 2001, they saw the potential as largely empty and wouldn’t pay a dime for it, given that the industry’s capacity vastly exceeded its current needs and no one could imagine the excess being absorbed in their lifetime. This cycle in investors’ willingness to value the future is one of the most powerful cycles that exists.”

- Unemotional people will have a better time investing because they are not as easily moved by fear and greed.

- Investments that seem riskier appear like they will make higher returns. But if high-risk assets always gave higher returns, they wouldn’t be high risk.

- Once people take a big loss in the market after buying an overpriced asset or bubble they get a new investing psychology: extreme risk aversion.

- Credit cycle summary: Prosperity leads to expanded lending, which leads to unwise lending, which leads to large losses, which makes lenders stop lending, which ends prosperity. And the cycle continues.

- In good times, lenders will lend with reduced interest rates (to make it a better deal for borrowers) and investors may buy stocks at a higher PE ratio (lending out their money at a lower value). When lenders (and investors) are eager to lend, it makes them more likely to accept losers (bad borrowers, bad companies, or overpriced stocks).

- In making investments, it has become my habit to worry less about the economic future—which I’m sure I can’t know much about—than I do about the supply/demand picture relating to capital. Being positioned to make investments in an uncrowded arena conveys vast advantages. Participating in a field that everyone’s throwing money at is a formula for disaster.

- The 2008 Financial crisis occurred because people got large housing loans who shouldn’t have (because banks were eager to loan): “In an extreme example of this trend, the category of “sub-prime” mortgages was created for borrowers who couldn’t satisfy traditional lending standards in terms of employment or income, or who chose to pay higher interest rates rather than document these things. The fact that weak borrowers like these could borrow large sums was indicative of irrational credit market conditions."

- It is best to buy a home or start a lease during bad economic times.

- Real estate is widely considered one of the best long-term investments, but it's not. Between 1628 and 1973, real property values—adjusted for inflation—went up a mere 0.2% per year. It’s only in recent years, Shiller says, that huge increases in real-estate prices have become the norm and that people have come to expect them.

- The costs of real estate: taxes, insurance, maintenance, interest payments, and opportunity costs.

- “The early discoverer—who by definition has to be that rare person who sees the future better than others and has the inner strength to buy without validation from the crowd—garners undiscovered potential at a bargain price.”

- “Financial disaster is quickly forgotten. In further consequence, when the same or closely similar circumstances occur again, sometimes in only a few years, they are hailed by a new, often youthful, and always supremely self-confident generation as a brilliantly innovative discovery in the financial and larger economic world.”

- Don’t wait for the market to fully bottom before you start buying. Instead, buy when the price is below intrinsic value.

- “Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

- “The important lesson is that—especially in an interconnected, informed world—everything that produces unusual profitability will attract incremental capital until it becomes overcrowded and fully institutionalized, at which point its prospective risk-adjusted return will move toward the mean (or worse).”

- Don’t confuse brains with a bull market.

- Short-term investment return is usually a popularity contest.

- Many people claim that the future will be different (due to changes in economics, psychology, or technology) but they are always wrong.

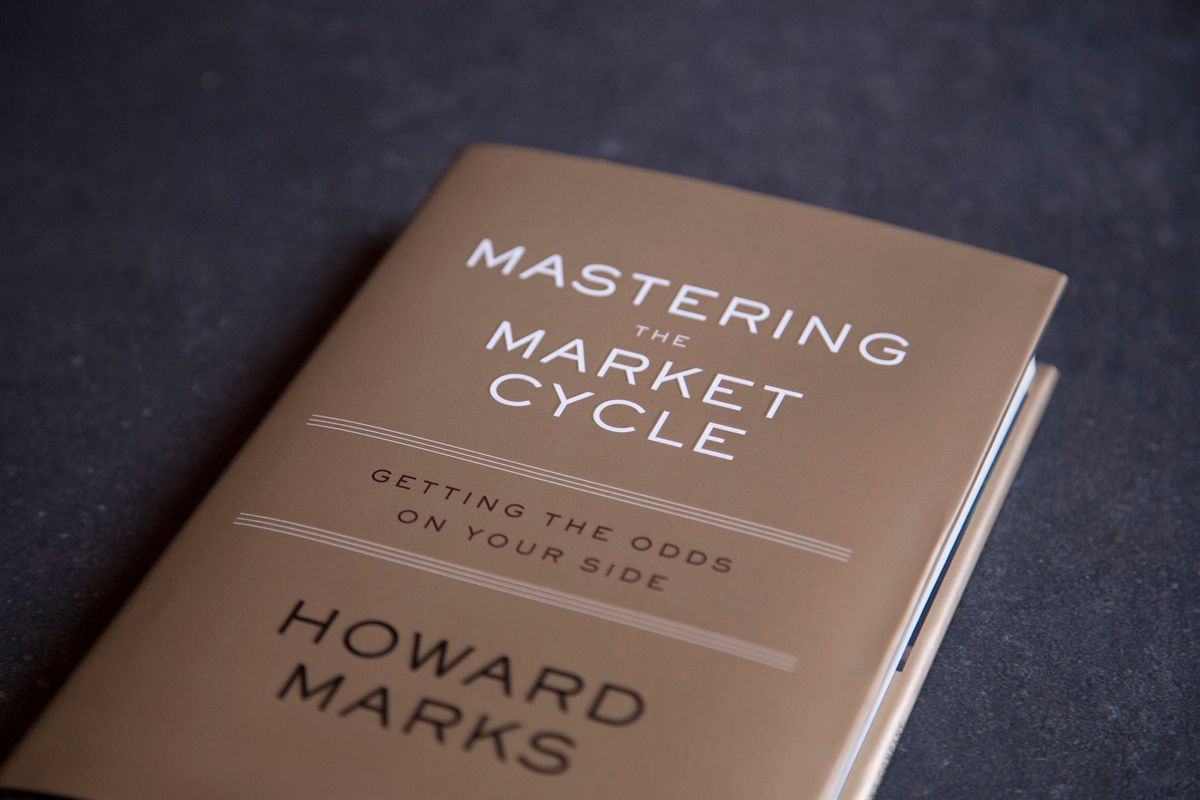

Chapter 1

Why Study Cycles?

Marks says 99% of investors (including Marks himself) cannot get an edge by analyzing the macro environment. The 99% of investors should instead focus on:

- Trying to know more than others about what I call “the knowable”: the fundamentals of industries, companies, and securities (deep dive).

- Being disciplined as to the appropriate price to pay for participation in those fundamentals (margin of safety/when to buy and sell).

- Understanding the investment environment we’re in and deciding how to strategically position our portfolios for it (risk management).

This book mostly covers #3.

The two kinds of risk:

- The likelihood of permanent capital loss.

- Opportunity risk. The likelihood of missing out on potential gains.

In short, risk is the probability of things not going the way we want.

Modern portfolio theory claims that risk is volatility. This is clearly false.

Our position in cycles changes the probabilities of future events. If the market has risen greatly, it is more likely to have a correction next.

Cycles are almost the same as pendulums. They swing one way and then another.

Chapter 2

The Nature of Cycles

Cycles are not clear cut. They can start or end in a bear or bull market.

Everything that happens today is the culmination of a long history. The roots of events happening today started hundreds of years ago—maybe even thousands of years ago (Christianity).

Generally, if there is a huge rise, a fall will occur and vice versa. Regression toward the mean is a general rule of market cycles.

Study the events of the past and be aware of the cyclical nature of things.

Study the dot com bubble and 2008 financial crisis.

Upward swings are not merely followed by corrections. They cause corrections. Imagine the stock gets heavier as it goes up. The higher it goes up the more weight it has and eventually gravity brings it back down—but it goes past the midway point and goes below it became it has momentum going down.

There are multiple cycles that go on at once and they all impact each other.

Success carries the seeds of failure and failure carries the seeds of success.

Chapter 4

The Economic Cycle

The economic cycle aka the business cycle. The more the economy rises, the more likely companies will expand their profits, and stock markets will rise.

- A good economy makes stocks go higher because businesses make more money.

GDP = (hours worked) x (value of production).

We expect GDP growth to be 2-3% annually.

Population growth is the main reason we expect GDP to increase annually.

Unemployment matters because those people are not contributing to GDP and they likely do not have as much money to spend.

Automation reduces GDP because fewer people are working.

Growing nations, China, for example, create a lot of products for the world. This increases their GDP but it decreases GDP for counties importing Chinese goods because they otherwise would have had to manufacture them themselves (and thus would have had higher GDP).

Gains in productivity and population are slowing in the US. GDP growth will likely be slower in the coming years.

India is likely to be the next China. And Nigeria and Bangladesh after India.

The willingness of the population to work can cause short-term changes to GDP. Over the long run, GDP is more based on population growth though.

World events can cause fear which can cause people to not purchase goods. Ex) 2008 financial crisis.

Good times, asset appreciation, presidential elections, etc can change how much people want to spend their money.

Inventories lead to ups and downs. When people don’t buy as much, companies have extra supply which is then added to inventory and they decrease production (no need to keep high production if you have inventory not yet sold). But then their inventory runs out and they will have too little production. This causes them to ramp up production which brings us back to where we started (companies have extra supply).

Success in investing is not only about being correct, it is about being more correct than others. If everyone thinks one asset is great, then it won’t perform as well as a contrarian but correct investment.

- Most contrarian investments are incorrect and therefore lead to being below average.

Chapter 5

Government Involvement with the Economic Cycle

On central banks and treasury manipulation of markets.

If the economy gets too high, a crash is bound to happen. If the economy gets too low, companies lose profits and people lose their jobs. It is the job of central bankers and treasury officials to manage economic cycles.

Central banks

Central banks (like the Fed) mainly exist to control inflation.

Causes of inflation:

- When the demand for goods increases relative to the supply, there can be “demand-pull” inflation.

- When inputs to production such as labor and raw materials increase in price, there can be “cost-push” inflation.

- Finally, when the value of an importing country’s currency declines relative to that of an exporting country, the cost of the exporter’s goods can rise in the importing country.

The cost of goods can escalate for any of the reasons above. That’s inflation. But, as I just said, sometimes these events can occur without an accompanying acceleration of inflation. And sometimes inflation can increase without these things being present. There is a large psychological component that influences all of this.

“Since inflation results from economic strength, the efforts of central bankers to control it amount to trying to take some of the steam out of the economy. They can include reducing the money supply, raising interest rates, and selling securities. When the private sector purchases securities from the central bank, money is taken out of circulation; this tends to reduce the demand for goods and thus discourages inflation.”

- The problem here is that these methods limit the growth of the economy.

“The issue is complicated by the fact that in the last few decades, many central banks have been given a second responsibility. In addition to controlling inflation, they are expected to support employment, and, of course, employment does better when the economy is stronger. So central banks encourage this through stimulative actions such as increasing the money supply, decreasing interest rates, and injecting liquidity into the economy by buying securities—as in the recent program of “quantitative easing.” Central bankers who focus strongly on encouraging employment and lean toward these actions are called “doves.”

“The bottom line is that most central bankers have two jobs: to limit inflation, which requires restraining the growth of the economy, and to support employment, which calls for stimulating economic growth.”

- “So the job of the central banker is to behave appropriately counter-cyclically: that is, to limit the extent of cycles, slowing the economy in times of prosperity in order to keep inflation under control, and stimulating the economy during slowdowns to support employment.”

Governments

“Governments have a greater variety of responsibilities than central bankers, only a small portion of which are related to the economic matters. Like central banks, they also are charged with stimulating the economy when appropriate, albeit not directly with controlling inflation. In their work with the economy, treasuries, too, are concerned with regulating the cycle: not too fast and not too slow.”

“Governments’ main tools for managing the economic cycle are fiscal, defined as being concerned primarily with taxing and spending. Thus when governments want to stimulate their countries’ economies, they can cut taxes, increase government spending and even distribute stimulus checks, making more money available for spending and investment. On the other hand, when they think economies are growing so fast as to be at risk of overheating—setting the scene for a resulting slowdown—governments can increase taxes or cut spending, reducing demand in their economies and thereby slowing economic activity.”

“The ultimate topic under this heading concerns national deficits. In the distant past, most governments ran balanced budgets. In short, they weren’t able to spend more money than they brought in through taxes (or conquests). But then the concept of national debt arose, and the ability to incur debt introduced the potential for deficits: that is, for governments to spend more than they take in.”

In the 1930s, Keynes told the government to stimulate the weak economy by running deficits. And to run surpluses when the economy is strong. This removes funds from the economy, discouraging spending and investing. But spending less than you bring in attracts fewer votes than do generous spending programs. Thus surpluses have become as rare as buggy whips.

Chapter 6

The Cycle in Profits

Effects of GDP and the economic cycle on different sectors:

- Sales of industrial raw materials and components are directly responsive to the economic cycle. When business collectively increases its output—that is, when GDP expands—it takes more chemicals, metals, plastic, energy, wire, and semiconductors to do so, and vice versa.

- On the other hand, everyday necessities like food, beverages, and medicine aren’t highly responsive to the economic cycle. People generally consume them regardless of what’s going on in the economy. (But demand isn’t absolutely constant: people trade down in recessions—buying cheaper food and eating at home rather than in restaurants—and they trade up in times of prosperity. And, sadly, people who are struggling financially may cut down even on their consumption of “necessities” when forced to choose between food, medications, and rent payments.)

- Demand for low-cost consumer items (like everyday clothing, newspapers and digital downloads) isn’t very volatile, while demand for luxury goods and vacation trips may be.

- Purchases of big-ticket “durable goods”—things like cars and homes for individuals and trucks and factory equipment for businesses—are highly responsive to the economic cycle. First, the fact that they’re durable means they last a long time, so replacement can be deferred in times of economic weakness. Second, because they cost a lot, they’re hard to afford in bad times and easier to afford good times. And third, businesses generally need more of them when business is good and less when it isn’t. These things make the demand for durables highly responsive to the economic cycle.

- Demand for everyday services generally isn’t volatile. If they’re necessary (like transportation to work) and low-priced (like haircuts), demand won’t be highly sensitive to changes in the economy. Further, services like these have a limited shelf life and can’t be stored. Thus they have to be purchased continually. But demand still can vary based on economic conditions: for example, a haircut can be made to last five weeks rather than three.

“For the most part, however, economic growth dominates the process through which sales are determined. Sales generally rise strongly when GDP growth is strong and less so (or they decline) when it isn’t.”

Not all companies make more money with scale. Sometimes the costs of increasing production outweigh the profit.

Operating leverage is when scaling sales increases your profit margin. This scaling is good in good times. But in bad times you don’t make enough to pay for everything.

Companies respond to sales declines by laying off workers and closing stores.

Individual composition of a business, taxes and regulations, weather, war, and fads determine a business’ sales more than economic cycles, though economic cycles do impact them (more greatly in different sectors or industries).

Marks says that newspapers were still around in the 90s. People thought they were “defensive” stocks that wouldn’t go anywhere. But then the internet disrupted them.

- “But isn’t technology cyclical itself? Technologies are born, they prosper, and then they are replaced by still newer ones.”

Chapter 7

The Pendulum of Investor Psychology

“In 1999, investors accepted at face value their telecom companies’ rosy predictions of the future, and they were willing to pay handily for that potential. But in 2001, they saw the potential as largely empty and wouldn’t pay a dime for it, given that the industry’s capacity vastly exceeded its current needs and no one could imagine the excess being absorbed in their lifetime. This cycle in investors’ willingness to value the future is one of the most powerful cycles that exists.”

The costs of real estate: taxes, insurance, minimum maintenance, interest payments, and opportunity costs.

Human Psychology: “Rational? Where do these folks live? Even 50 years ago, experimental studies were demonstrating that people stay with clearly wrong decisions rather than change them, throw good money after bad, justify failed predictions rather than admit they were wrong, and resist, distort or actively reject information that disputes their beliefs.”

Unemotional people will have a better time investing because they are not as easily moved by fear and greed.

“A few years ago my friend Jon Brooks supplied this great illustration of skewed interpretation at work. Here’s how investors react to events when they’re feeling good about life (which usually means the market has been rising):

Strong data: economy strengthening—stocks rally

Weak data: Fed likely to ease—stocks rally

Data as expected: low volatility—stocks rally

Banks make $4 billion: business conditions favorable—stocks rally

Banks lose $4 billion: bad news out of the way—stocks rally

Oil spikes: growing global economy contributing to demand—stocks rally

Oil drops: more purchasing power for the consumer—stocks rally

Dollar plunges: great for exporters—stocks rally

Dollar strengthens: great for companies that buy from abroad—stocks rally

Inflation spikes: will cause assets to appreciate—stocks rally

Inflation drops: improves quality of earnings—stocks rally”

- The opposite is true (stocks crash) when people are feeling bad about life.

Chapter 8

The Cycle in Attitudes Toward Risk

Investments that seem riskier appear like they will make higher returns. But if high-risk assets always gave higher returns, they wouldn’t be high risk.

Once people take a big loss in the market after buying an overpriced asset or bubble they get a new investing psychology: extreme risk aversion.

Chapter 9

The Credit Cycle

When the credit window is open (like the window at a bank teller), it is easy to get loans. But when it is closed it is difficult or impossible to get loans. This is hugely influenced by psychology and market sentiment. It has huge effects on what will happen in the economy. Ex) Businesses can’t scale without capital to invest.

The credit window can be open and then immediately fall.

It is best to sign up for a credit card when the credit window is open. This is usually when the economy is good and there is no talk of an impending recession or crash.

A closed credit market causes fear to spread.

Even big businesses can default if they don’t have enough cash on hand to pay back a creditor when they call for their money back when the credit window closes. Essentially, even big businesses can get margin called when the markets go down.

Credit cycle summary: Prosperity leads to expanded lending, which leads to unwise lending, which leads to large losses, which makes lenders stop lending, which ends prosperity. And the cycle continues.

In good times, lenders will lend with reduced interest rates (to make it a better deal for borrowers) and investors may buy stocks at a higher PE ratio (lending out their money at a lower value).

- When lenders (and investors) are eager to lend, it makes them more likely to accept losers (bad borrowers, bad companies, or overpriced stocks).

In the financial world, if you offer cheap money, they will borrow, buy (assets—or worse, goods) and build (companies)—often without discipline, and with very negative consequences.

“In making investments, it has become my habit to worry less about the economic future—which I’m sure I can’t know much about—than I do about the supply/demand picture relating to capital. Being positioned to make investments in an uncrowded arena conveys vast advantages. Participating in a field that everyone’s throwing money at is a formula for disaster.”

The 2008 Financial crisis occurred because people got large housing loans who shouldn’t have (because banks were eager to loan): “In an extreme example of this trend, the category of “sub-prime” mortgages was created for borrowers who couldn’t satisfy traditional lending standards in terms of employment or income, or who chose to pay higher interest rates rather than document these things. The fact that weak borrowers like these could borrow large sums was indicative of irrational credit market conditions."

- Relaxed credit diligence on the part of mortgage lenders, and the availability to home buyers of generous sub-prime financing, made home ownership possible for more Americans.

- People were eager to get these variable-rate loans because they were supposed to be a new financial discovery that allowed them to get the home of their dreams.

“In a speech in October 2002, President George W. Bush repeated what he’d been told by one of his friends: “You don’t have to have a lousy home for the first-time home buyers. If you put your mind to it, the first-time home buyer, the low-income home buyer can have just as nice a house as anybody else.” I wonder if the people who heard that statement at the time found it as illogical as it seems today.”

“In late 2008 everyone threw in the towel on everything. The prices of all assets other than Treasurys and gold collapsed.”

“And, ultimately, market participants demonstrated that when negative psychology is universal and “things can’t get any worse,” they won’t.”

An uptight, cautious credit market usually stems from, leads to, or connotes things like these:

- fear of losing money

- heightened risk aversion and skepticism

- unwillingness to lend and invest regardless of merit

- shortages of capital everywhere

- economic contraction and difficulty refinancing debt

- defaults, bankruptcies and restructurings

- low asset prices, high potential returns, low risk, and excessive risk premiums

- Note: this is a great time to invest

A generous capital market is usually associated with the following:

- fear of missing out on profitable opportunities

- reduced risk aversion and skepticism (and, accordingly, reduced due diligence)

- too much money chasing too few deals

- willingness to buy securities in increased quantity

- willingness to buy securities of reduced quality

- high asset prices, low prospective returns, high risk and skimpy risk premiums

- Note: this is a bad time to invest

Chapter 10

The Distressed Debt Cycle

When times are good, lenders lend to risky borrowers. This “stacks logs in the fireplace for the next bonfire.”

“In short—and to over-simplify—when a company goes through bankruptcy, the old owners are wiped out and the old creditors become the new owners.”

They’re looking for a good company with a bad balance sheet that is about to go bankrupt or already has.

“A distressed debt investor tries to figure out (a) what the bankrupt company is worth (or will be worth at the time it emerges from bankruptcy), (b) how that value will be divided among the company’s creditors and other claimants, and (c) how long this process will take. With correct answers to those questions, he can determine what the annual return will be on a piece of the company’s debt if purchased at a given price.”

Distressed debt investors love when credit is given out because this makes the market frothy with businesses who have borrowed money. This “stacks logs in the fireplace” then, when a recession comes, the fireplace gets lit and all of these companies burn down (go bankrupt). This allows for huge possible returns for distressed debt investors. This is because the credit window closes in a recession, so these companies cannot borrow to keep operations running. Investors are now risk-adverse and not wanting to invest. The slower economy can mean lower revenue.

Chapter 11

The Real Estate Cycle

In good times, people can usually make a business or get a loan or buy a stock quickly but you cannot develop real estate as fast. You have to find land, plan it, develop it, etc. This can take years. This makes the real estate market different than other more liquid markets.

Bad times cause people to not want to build more housing. Then when times are good people look for housing but none has been developed. This increases rents and house prices. This makes it more attractive for investors to make houses, so they start building. Because there are good times, the credit window is open so these builders can get loans for their projects. The projects developed more quickly fill that high demand and this makes the investors and builders eager to make more. The news headlines say it’s a good time to build. Then 'everyone' starts developing real estate. Most of the projects started now have years until completion—and they will likely be finished in bad times, when rent and housing prices are low.

This shows that it is best to get housing (buy a home, start a lease) during bad times.

“Neighborhoods and whole cities go in and out of favor over time, affecting the value of homes. For this reason, statements about homes in a given city or neighborhood wouldn’t necessarily be applicable to homes in general.”

“That is to say, where everyone from your wise old uncle to the broker who sold you your house holds it as gospel that real estate is one of the best long-term investments, this longest of long-term indices suggests that, on the contrary, it sort of stinks. Between 1628 and 1973 (the period of Eichholtz’s original study), real property values on the Herengracht—adjusted for inflation—went up a mere 0.2 percent per year, worse than the stingiest bank savings account. It’s only in recent years, Shiller says, that huge increases in real-estate prices have become the norm and that people have come to expect them. If this description of the past few years [in which “prices just went up amazingly”] typifies the brave new world we live in, putting it into the perspective of time—rise, fall, rise, fall—leads us back to what may be the oldest history lesson of all: it tends to repeat."

“It’s not for nothing that they often say cynically—in tougher times, when optimistic generalizations can no longer be summoned forth—that “only the third owner makes money.” Not the developer who conceived and initiated the project. And not the banker who loaned the money for its construction and then repossessed the project from the developer in the down-cycle. But rather the investor who bought the property from the bank amid distress and then rode the up-cycle.

Of course this is an exaggeration, like all generalizations. But it does serve as a reminder of the relevance of cyclicality to the real estate market, and especially of the way cyclicality can function in the less-good times.”

Chapter 12

Putting it All Together—The Market Cycle

“What the wise man does in the beginning, the fool does in the end.”

- Be early.

“The early discoverer—who by definition has to be that rare person who sees the future better than others and has the inner strength to buy without validation from the crowd—garners undiscovered potential at a bargain price.”

Chapter 13

How to Cope with Market Cycles

“Financial disaster is quickly forgotten. In further consequence, when the same or closely similar circumstances occur again, sometimes in only a few years, they are hailed by a new, often youthful, and always supremely self-confident generation as a brilliantly innovative discovery in the financial and larger economic world.”

“In fact, most bubbles, if not all, are characterized by the unquestioning acceptance of things that have never held true in the past; of valuations that are dramatically out of line with historic norms; and/or of investment techniques and tools that haven’t been tested.”

Marks recommends not waiting for the market to fully bottom before you start buying:

“First, there’s absolutely no way to know when the bottom has been reached. There’s no neon sign that lights up. The bottom can be recognized only after it has been passed, since it is defined as the day before the recovery begins. By definition, this can be identified only after the fact.

And second, it’s usually during market slides that you can buy the largest quantities of the thing you want, from sellers who are throwing in the towel and while the non-knife-catchers are hugging the sidelines. But once the slide has culminated in a bottom, by definition there are few sellers left to sell, and during the ensuing rally it’s buyers who predominate. Thus the selling dries up and would-be buyers face growing competition.”

“So if targeting the bottom is wrong, when should you buy? The answer’s simple: when price is below intrinsic value. What if the price continues downward? Buy more, as now it’s probably an even greater bargain. ”

In short, when the market is high in its cycle, they should emphasize limiting the potential for losing money, and when the market is low in its cycle, they should emphasize reducing the risk of missing opportunity.

How? Try to travel into the future and look back. In 2023, do you think you’re more likely to say, “Back in 2018, I wish I’d been more aggressive” or “Back in 2018, I wish I’d been more defensive”? And is there anything today about which you’d be likely to say, “In 2018, I missed the chance of a lifetime to buy xyz”? What you think you might say a few years down the road can help you figure out what you should do today.”

We do not know how long cycles will last.

Chapter 14

Cycle Positioning

The formula for investment success should be considered in terms of six main components, or rather three pairings:

1. Cycle positioning—the process of deciding on the risk posture of your portfolio in response to your judgments regarding the principal cycles.

2. Asset selection—the process of deciding which markets, market niches, and specific securities or assets to overweight and underweight.

- Positioning and selection are the two main tools in portfolio management. It may be an over-simplification, but I think everything investors do falls under one or the other of these headings.

3. Aggressiveness—the assumption of increased risk: risking more of your capital; holding lower-quality assets; making investments that are more reliant on favorable macro outcomes; and/or employing financial leverage or high-beta (market-sensitive) assets and strategies.

4. Defensiveness—the reduction of risk: investing less capital and holding cash instead; emphasizing safer assets; buying things than can do relatively well even in the absence of prosperity; and/or shunning leverage and beta.

- “The choice between aggressiveness and defensiveness is the principal dimension in which investors position portfolios in response to where they think they stand in the cycles and what that implies for future market developments.”

5. Skill—the ability to make these decisions correctly on balance (although certainly not in every case) through a repeatable intellectual process and on the basis of reasonable assumptions regarding the future. Nowadays this has come to be known by its academic name: “alpha.”

6. Luck—what happens on the many occasions when skill and reasonable assumptions prove to be of no avail—that is, when randomness has more effect on events than do rational processes, whether resulting in “lucky breaks” or “tough luck.”

- “Skill and luck are the prime elements that determine the success of portfolio management decisions. Without skill on an investor’s part, decisions shouldn’t be expected to produce success. In fact, there’s something called negative skill, and for people who are saddled with it, flipping a coin or abstaining from decisions would lead to better results. And luck is the wildcard; it can make good decisions fail and bad ones succeed, but mostly in the short run. In the long run, it’s reasonable to expect skill to win out.”

Chapter 15

Limits on Coping

“Being too far ahead of your time is indistinguishable from being wrong.”

Chapter 16

The Cycle in Success

“The important lesson is that—especially in an interconnected, informed world—everything that produces unusual profitability will attract incremental capital until it becomes overcrowded and fully institutionalized, at which point its prospective risk-adjusted return will move toward the mean (or worse).”

Don’t confuse brains with a bull market.

Bargains are usually found in things easy to comprehend, unusual, and easily dismissed by the crowd. Short-term investment return is usually a popularity contest.

The “best” investments change over time:

- Cheap small-caps outperform until they reach the point where they’re no longer cheap.

- Trend-following or momentum investing—staying with the winners—works for a while. But eventually, rotation and buying the laggards takes over as the winning strategy.

- "Buying the dips” lets investors take advantage of momentary weakness, up until the time when a major problem surfaces (or the market simply no longer recovers), causing price declines to be followed by further price declines, not quick rebounds.

- Risky assets outperform—coming from valuations where they were excessively penalized for their riskiness—until they’re priced more like safe assets. Then they underperform until they once again offer adequate risk premiums.

Paradoxically, things that have performed poorly can be the most likely to perform in the future.

Chapter 17

The Future of Cycles

Marks says that many people claim that the future will be different (due to changes in economics, psychology, or technology) but they are always wrong. Cycles will never end because that would require people to be completely rational and emotionless—things that humans can never be. Note: unless AI takes over all decisions.

Comments ()